To Stretch or Not to Stretch?

Curently there is a lot of discussion on the usefulness of stretching both from a therapeutic and preventive standpoint. Read more about the controversy.

Regular stretching can be effective for increasing or maintaining the range of motion of a joint or limb. Stretching is also frequently promoted as an integral part of any exercise session to improve performance, prevent injuries and reduce delayed onset muscle soreness. Research is mixed on suporting stretching to improve performance or for reducing injuries and delayed onset muscle soreness. In fact, there has been some discussion that static stretching leads to an acute loss of strength and power, also known as stretch induced strength loss.

There are several different types of stretching, static, dynamic, ballistic and neuromuscular facilitation type stretching are those that have been most studied. Static stretching involves lengthening a muscle and holding it in a mildly uncomfortable position for a period, usually somewhere between 10 and 30 seconds. Dynamic stretching uses momentum and active muscular effort to lengthen a muscle, but the end position is not held. PNF stretching typically involves a contraction of the opposing muscle to stretch the target muscle, followed by a contraction of the target muscle.

Does Stretching Prevent Injury?

There still exists beliefs that stretching before exercise prevents injury. Many research studies to date have been reviewed and results do not demonstrate that stretching prevents injury. A good warm up and some dynamic mobility exercise that is sports specific might yield the best outcomes for preventing injuries.

Does Stretching Improve Performance?

In fact, long periods of static stretching ( greater than 15 sec holds for several repetitions) may impair muscle performance when it comes to strength and power type activities (heavier resistance activities, or a quick bursts of maximal effort). There seems to be a decline in abilities to perform these activities with static stretching. Similiarly with speed and agility dominant activites like sprinting or changing direction quickly, performance declines with enough static stretching. Stretching prior to endurance activities either have no to a slight decline in performance effect. Using a warm up, or using dynamic stretching reduces any decline in performance.

Does Stretching Increase Flexibility or Muscle Elongation?

Studies performed on hamstring muscles have demonstrated increases in flexibility and range of motion from a stretch, but does it result from muscle elongation or a reduction in muscle stiffness? Actual changes to muscle’s elastic and fluid properties ( viscoelastic deformation) are transient in humans, and have no effect on subsequent stretching sessions. More long term studies of stretching, 3-8 week, suggest that increased extensibility is a result of altered sensation to stretch more than actual changes in muscle length.

Can Stretching be Used to Manage Pain?

Short term pain relief can be realized from stretching for some tissues. Pain may be mediated more from general movement and so looking at mobility over stretching could explain why we see relief from this sort of activity. Pain reduction with movement can often be explained by the effect it has on our nervous system, more than the tissues itself. When it comes to managing tendons, too much compression from stretching can increase pain and irritability depending on the stage of the injury.

So What Can Stretching Do and Should you Do it?

Stretching can increase flexibility in the short and long term, but whether there are changes in the muscle architecture is debatable, unless aggressive and prolonged.

Prolonged static stretching should probably not be performed before strength and power type activites, and a more dynamic type stretch and warm up may enhance performance and reduce risk of injury.

Stretching can be looked at as neither significantly good or bad. In terms of best use of time, there may be better other types of exercise for gaining benefits to health and ability.

That said, if it’s an important part of your routine that you value, it feels good and imparts percieved improvement in performance in the short term, it does not need to be eliminated especially depending on what you are using it for. Stretching at the end of a weight or power training activity, instead of before is recommended.

Resources:

What Stretching Does and Does Not Do? Jarod Hall, DPT PhysioNetwork Blog

Whepper, C. et al. Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation; Physical Therapy 90(3), March 2010.

The Skinny on Carbohydrates.

Diet advice is a dime a dozen, which often makes it difficult to know what’s right, what’s wrong, what works, and what doesn’t. With respect to carbohydrates in the diet, “expert” recommendations vary from “eat as little as possible” to “make 65-70% of your calories carbohydrate foods”. With a range of recommendations that varied, how can we really assess the best carb guidance for ourselves?

Here are a few rules of thumb:

Not all carbs are created equal: Seek out nutrient dense carbs, foods that are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Fruits, whole grains, some starchy vegetables are good examples. Non-nutrient dense carbs like candy and soda pop, which contain sugar (a carbohydrate) but not much additional nutrition, should of course be eaten sparingly.

First and foremost, carbs provide energy. Many carbs contain vitamins and minerals (as mentioned above), but their first role in the body is energy provision to keep the brain, muscles, and other organs functioning properly. If you’re sitting on the couch all day and don’t require much energy, you don’t need as much carb. If you’re performing physical activity, however, your need for carbs increases. So a viable way to think of daily carb needs is, “You burn it- -you earn it.” On a day when you’re going to be particularly active, save a bit more room on your plate for carb-containing foods. On a not-so-active day, put fewer carbs on the plate. Athletes in-season need more carbs. In the off season, or when sidelined by injury, their carb needs may be adjusted down accordingly.

Dietary fat also provides energy, so why not adhere to a high fat, ketosis-style diet, and keep the carbs off the plate? While somewhat controversial, most health experts will tell you your diet should contain at least 40-50% calories from carbs, if not more. When carbs aren’t present and reliance on fat for energy increases, one tends to develop ketosis, a condition often marked by lethargy, fatigue, and mental confusion. A combination of carbs and fat in the diet allows the body to function more efficiently, as well as to preserve muscle protein.

But will carbs make me fat? Too much of any calorie-containing food may lead to weight gain. Carbs in particular have been called out lately, largely because of the weight loss success some people experience when cutting carbs from the diet. While it’s true that carb cutting may lead to rapid, sometimes significant weight loss it must be remembered that much of this initial loss is water loss. For every gram of carb you store, you store a near equal amount of water. Cut the carbs, you lose the water; your weight goes down-transiently. This rapid weight loss is really “Fool’s Gold”. It’s water, not body fat you’re losing. For real, sustained weight loss a prudent diet with moderate amount of carb, fat, protein is best.

Finally, recent studies suggest that a muscle depleted of its carb via habitual exercise, a low carb diet, or both, may be more prone to injury and less responsive during exercise recovery than a muscle with adequate carb reserves. If you exercise, it’s important to maintain some level of carb in the diet to be able to exercise effectively, at a higher intensity, and to recovery properly to set yourself up for the next day’s activity. That said, other research suggests that too much sugar in the diet may increase inflammation and exacerbate soft tissue and joint pain. So, the right balance of carbs is essential. More high-quality carbs, less sugar is the best way to go.

Nutrition research continues to evolve, and our perspectives about what constitutes a healthy mix of nutrients in the diet has changed over the years as well. Based on the best available evidence, a varied diet that contains a healthy mix of carbs (~55% of kcals), fats (~30% of kcals), and proteins (~15% of kcals) is best to avoid injury, maintain health, and be able to perform physical activity longer and harder. Of course this advise will require individualization for each person’s specific needs.

Mitch Kanter, PhD has served as Director of Health & Nutrition for Cargill and General Mills, and as Director of the Gatorade Sports Science Institute. He currently serves as Chief Science Officer for the Global Diary Platform, and as an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota.

No Time to Lift Weights?

While you may think strength training is not for you, you are too old to start, or you don’t have time or equipment, there are many ways to get this done with lots of options to take advantage of. Strength training is as important as cardiovascular exercise from a health perspective. Muscle weakness, termed sarcopenia and dynapenia, is a normal age-related phenomenon, occurring at a rate of 1% to 5% annually from the age of 30. Losing strength as we get older is potentially debilitating. Sarcopenia or muscle mass loss can lead to falls, a decline in function and a host of metabolic changes resulting in a higher prevalence of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, poor blood cholesterol and fat levels, and high blood pressure.

Strategies for efficient gains in strength

While you may think strength training is not for you, you are too old to start, or you don’t have time or equipment, there are many ways to get this done with lots of options to take advantage of. Strength training is as important as cardiovascular exercise from a health perspective. Muscle weakness, termed sarcopenia and dynapenia, is a normal age-related phenomenon, occurring at a rate of 1% to 5% annually from the age of 30. Losing strength as we get older is potentially debilitating. Sarcopenia or muscle mass loss can lead to falls, a decline in function and a host of metabolic changes resulting in a higher prevalence of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, poor blood cholesterol and fat levels, and high blood pressure.

Many Ways to Get at It

Muscle requires an adequate stimulus, or overload, to get stronger. Similar to the cardiovascular system, skeletal muscle requires a workload of approximately 60% of maximum available strength, to increase in strength. This starting point will obviously be different for everyone. Long lasting and significant change in strength occurs over a 12 to 16 week period.

Strength gains can be achieved through a wide spectrum of intensities. Lower weights with higher repetitions can be as effective in gaining strength, as higher weights with fewer repetitions.

Higher loads with fewer reps are going to be most effective for making strength gains in a time efficient manner. Here training to fatigue or failure is less important. Deciding which is best for you depends on your goals. To perform everyday activites at a minimum, the higher repetiton with a lower load may be sufficient. This is also practical when you don’t have a lot of heavier home equipment.

Ideal Volume

Ideal are 4- 10 sets per week for each muscle group. Since less volume is needed to maintain strength gains than to gain strength, you could ramp up your sets/week at certain times of the year and then ramp down to maintain. Because training frequency appears less important than maintaining a certain levels of volume, you can decide to spread those 4-10 sets out over 1-3 times/week for more time efficiency.

Warm Up and Stretching

Stretching need not be prioritized unless joint mobility is a goal, and can be done more dynamically as part of the strength training.

General warm up ( like 5-10 min on the bike or TM are ok with a time crunch) but specific muscle group warm ups are useful if you are doing heavier loads.

Drop Sets, Rest Pause Training and Supersets for increasing muscle mass gain with less time

Drop set training reduces rest between sets by using a lower load. It reduces total time of training but is best suited for single joint exercises.

Rest pause training is higher weight, shorter sets and short rests.

What do You Need to Maintain Strength

Younger adults can probably maintain muscle mass and strength by training with as little as one brief session per week, while older adults probably need somewhat more weekly volume. One session of 3-4 sets of each muscle group appears to be sufficient to maintain strength gains.

Machines vs Free Weights

While ultimately this may be a personal preference, they both have pros and cons for efficiency. For someone not accustomed to strength training, machine are more efficient from a technique standpoint, but may require waiting to use. For someone more experienced in weight training, free weights can be used for multiple exercises. Free weights are more practical for home use. A mix of both is another option. Using resistance bands and body weight can be an alternative that is time efficent and easy at home. The challenge is finding the appropriate intensity as well as being able to progress while maintaining a good level of muscle activation, especially in the lower body. Still body weight exercises can be progressed but can get challenging. Recomendations for an ideal would be to use free weights or machines to do some training and use the bands and body weight as a supplement when traveling or when other equipment is not available. To quantify intensity with bands or body weight you can use a percieved exertion scale or a repetitions in reserve scale.

Types of Exercises

For time efficiency use both arms or legs and multiple muscle exercise that use large ranges of dynamic exercise. Warm ups should be exercise specific, meaning you do a lower load of a similiar or same exercise as the training exercise.

Muscle Power

Power is the ability to accelerate and move quickly. This can also become comprimised as we get older. After the age of 60, power loss is quicker and may have a bigger influence on physical function. This involves moving more quickly through one part of an exercise and then slowly through the other.

In summary, strength training can be made more time-efficient by prioritizing both sided, multi muscle movements through a full range of motion with ≥ 4 weekly sets per muscle group using an appropriate amount of weight, sets and reps. Using additional techniques like super sets can reduce time even further. Strength training can involve a variety of types of equipment. Use exercise specific warm ups, and prioritizing stretching is not necessary. Sessions should involve some power training, especially in the older adult. Lastly, strength training is a very important way to maintain muscle mass and avoid health declines.

Engage Physical Therapy and Wellness can help you get started getting stronger through individualized Physio-Fitness programs. An advantage of having a Physical Therapist partnering with you is we can adjust for and assist with painful conditions or injuries as we move through our program.

Resources:

Avers, D and M. Brown; Strength Training for the Older Individual. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy Vol. 32;4:09, 2009.

Iversen, V. et al. No Time to Lift? Designing Time‑Efcient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review.Sports Medicine (2021) 51:2079–2095

Is it Time to ReFrame How we think about Arthritis-Words and Behaviors that Harm?

For a lot of non- traumatic musculoskeletal pain, the anatomy does not explain it all. Structural changes we see on images are present in painfree individuals. The trend is driving surgical decisions while at the same time repairing, resurfacing and replacing structures too early, or perhaps unneccessarily, which is coming under critisism. This is not to say surgery is never necessary, but an alternative approach is worth exploring.

Words can influence how we think and act.

For a lot of non- traumatic musculoskeletal pain, the anatomy does not explain it all. Structural changes we see on images are present in painfree individuals. , is driving surgical decisions. At the same time repairing, resurfacing and replacing structures too early, or perhaps unneccessarily, is coming under critisism. This is not to say surgery is never necessary, but a conservative approach is worth exploring, as it can often be successful.

Exercise has gotten a bad rap around arthritis. Exercise is THE most effective treatment for early to mid stage arthritis. Exercise will not harm articular cartilage, the cartilage that lines the surface of your joint, and if anything might improve articular cartilage health.

Radiographic arthritis ( what we see on a picture) and clinical arthritis can be two different things that do not always match up. There is a large set of the population that may show signs of arthritis on imaging and have no pain whatsoever. Pain is complex and multifactorial, and we sometimes assume we know what is driving our pain. While everyone wants to know what is wrong with their knee or hip or other areas of the body, placing unneccesary labels and words that harm, like "degenerative", " bone on bone", " worst x-ray I have ever seen" , sets up a story for us that we are damaged and should not overdo, or do anything. Words have the ability to change how we think and how we move, and that may ultimately be less helpful.

In addition, the worry and distress of living with a chronic condition, leads us to seek answers on the internet, from friends or other sources. This can be a challenge in the world of online misinformation and often confirms for someone, what may or may not be true or helpful. It also leads to discovery of promising treatments, that are often passive, and don’t really provide long term solutions.

If we managed arthritis like other chronic diseases, like diabetes for example, we would undertand that arthritis is influenced by many interacting factors. Factors like genetics, psychological, physical, social, and lifestyle factors, as well as other illnesses, may be why some people have joint changes over others, as well as why some people have pain in the face of arthritis, and others don’t. It’s not just wear and tear anymore.

For this reason, a good plan for managing, not curing arthritis, should include understanding the person in front of you, sitting down and creating a mutual plan that addresses good sleep, diet, stress management and movement. The profound benefits of engaging in a graduated program of physical activity cannot be emphasized enough. This will look different for everyone and needs to be approached with empathy, guidance and support.

We can be more resilient than we are sometimes led to believe. There is no magic cure, and there is overwhelming research to support a partnership that involves the individual mastering some self management. In the long run, this provides the best shot for good outcomes that don’t immediately have to involve surgery.

Words are of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind.” Rudyard Kipling

Physical Therapy for the Win in Managing Tendon Pain and Symptoms

Tendinopathy describes injury to a tendon that results in pain, weakness, sometimes inflammation, stiffness and a reduction in function and exercise tolerance. The most common overuse tendinopathies involve the rotator cuff, the inside or outside of the elbow, the hip ( gluteal tendon), the knee ( patellar tendon) and the ankle ( plantar fascia and tibialis posterior and achilles tendon). While overuse is a common mechanism of injury, interestingly tendons can undergo similiar changes/injury in association with the use of antibiotics known as fluoroquinolones, excessive corticosteroid use, metabolic diseases associated with lifestyle factors, and genetics.

Many different types of tendons involved in tendon irritation or injury

Tendinopathy describes injury to a tendon that results in pain, weakness, sometimes inflammation, stiffness and a reduction in function and exercise tolerance. The most common overuse tendinopathies involve the rotator cuff, the inside or outside of the elbow (extensor and flexor tendons), the hip ( gluteal tendon), the knee ( patellar tendon) and the ankle ( plantar fascia and tibialis posterior and achilles tendon). While overuse is a common mechanism of injury, interestingly tendons can undergo similiar changes/injury in association with the use of antibiotics known as fluoroquinolones, excessive corticosteroid use, metabolic diseases associated with lifestyle factors, and genetics.

Lower limb tendinopathies exceed the incidence of arthritis. Tendinopathies occur most commonly between the ages of 18-65. The prevalence increases with increasing age and is more common in women than men.

In non-athletic populations, risk factors include obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes, age, family history, weakness and limited or excessive joint mobility. These can all influence the ability to recover.

In sports, as well as everyday life activities, risk factors include overuse of a repetitive activity, a sudden increase in activity, a new unfamiliar activity, lack of adequate recovery, and certain medications (antibiotics in the fluroquinolone family and statins.)

Individuals working in certain occupations that involve heavy and/or repetitive activity, are at greater risk for developing tendinopathies. Genetic factors play an important role between repair and degeneration. Genetic variants have been reported to be associated with a risk for achilles tendinopathy.

Tendinopathy occurs when collagen break down exceeds collagen build up. Tendinopathy can begin as a pre-clinical disease where no symptoms are present but changes are occuring to the tendon cells. We do not know for sure what tips the scale into a painful worsening state for some and not others.

Tendinopathies present with soreness and stiffness in the mornings and after sitting or being still for periods of time. There is often tenderness to pressing on the tendons and certain pain provoking tests can confirm the diagnoses as well. Images are not usually necessary unless we are trying to differentiate another cause of the pain, in which case an ultrasound or MRI may be useful. Pre clinical symptoms can include stiffness or change in performance, and early detection is important for activity modification, especially in sport.

Recovery can take 6-12 months. Some preventive programs have appeared to be successful in reducing the incidence of tendinopathy in sport, and with certain occupations, but this still needs to be individualized.

Currently, exercise regimens, referred to as tendon loading programs, remain the most effective conservative approach in the treatment of tendinopathy. There is limited evidence that one type of program is superior to another and therefore again needs to be individualized.

Adjunct treatments to exercise include the use of corticosteroid injections (CSI) which is controversial and being used less. CSI may be associated with poor healing and the use of these injections is not recommended prior to rotator cuff repair surgery, as it increases the risk of re-tearing. In tennis elbow and achilles tendinopathy, there was no difference in those patients that did and did not receive injection.

Other treatments that have inconclusive results are PRP injections, low level lasar therapy ( some effectiveness for achilles and rotator cuff), shock wave therapy ( some effectiveness in achilles and patellar tendons). Topical use of glyceryl trinitrate is safe and shows some promise within 6 months of diagnoses. All of these treatment require further investigation. Still on the horizon is more investigation into pharmacological treatments and regenerative medicine.

Given the additional benefits of exercise, this would be my choice for a first line of defense. Let Engage Physical Therapy and Wellness help you navigate this issue.

Resource:

Illar, N.L., Silbernagel, K.G., Thorborg, K. et al. Author Correction: Tendinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7, 10 (2021).

What is Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain and How do we Manage it?

Rotator cuff related shoulder pain ( RCRSP) is very common and 40 % of people with this condition report symptoms of pain, poor sleep and loss of function after 12 months. Most people over the age of 45 have non traumatic RCRSP. RCRSP is also known as sub -acromial impingement syndrome, subacromial bursitis, rotator cuff tendinopathy and painful arc syndrome. Also part of the continuum of RCRSP are non traumatic rotator cuff tears. Rotator cuff tears are classified as full thickness, partial thickness, degenerative or traumatic. Massive rotator cuff tears are those where more than 1 of the 4 tendons of the rotator cuff has a full thickness tear.

Rotator cuff muscles and their tendons

Rotator cuff related shoulder pain ( RCRSP) is very common and 40 % of people with this condition report symptoms of pain, poor sleep and loss of function after 12 months. Most people over the age of 45 have non traumatic RCRSP. RCRSP is also known as sub-acromial impingement syndrome, subacromial bursitis, rotator cuff tendinopathy and painful arc syndrome. Also part of the continuum of RCRSP are non traumatic rotator cuff tears. Rotator cuff tears are classified as full thickness, partial thickness, degenerative or traumatic. Massive rotator cuff tears are those where more than 1 of the 4 tendons of the rotator cuff has a full thickness tear.

Risk factor for RCRSP include having a high BMI ( Body mass index), and metabolic diseases such as Diabetes and Heart Disease. Lifestyle factors that negatively impact RCRSP are smoking, low activity levels, and poor diet.

In most of these types of RCRSP, including RC tears of most kinds, best practice management is exercise based rehabilitation. This will look different for each individual. In addition rehab also is best when it includes education around the meaning of the pain, how tendons behave, and expectations for recovery. Rehabilitation requires a positive belief in your ability to execute the recomended treatment, motivation, and compliance, to improve outcomes. Passive treatments may lead to short term effects but are not recommended in the long term.

Exercise based strategies are as good as or better than surgery when it comes to managing rotator cuff related pain. These improvements are maintained at 1 year out. Recent studies using a “ sham surgery” compared to a real RC repair demonstrated the 2 groups faired the same with and without the actual surgery. Also many people have no symptoms with RC tears ranging from partial to full thickness, to even massive RC tears.

There has been much discussion about which types of exercises are best to manage RCRSP. The research in inconclusive but there are some general thoughts of best practice. A minimum of 12 weeks in needed to see changes with exercise. Some pain is expected. In fact individuals that exercise with some pain saw more increase in function. The program should be progressive so in the mid to long term, more resistance and more repetitions is helpful.

Individuals with symptomatic non-traumatic RC full and partial thickness tears are managed in a similiar way as noted above. Even with a full thickness tear, there is usually a lot of viable good tendon remaining. While research for exercise based management of massive RC tears is limited, conservative exercise based therapy is supported for this population as well.

Resources:

Hallgren HCB, Holmgren T, Öberg B, et al A specific exercise strategy reduced the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients; British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:1431-1436.

Miller J, et al. Association of Strength Measurement with Rotator Cuff Tear in Patients with Shoulder Pain: The ROW Study; Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016 January ; 95(1): 47–56.

Lee, W. et al; Clinical Outcomes of Conservative Treatment and Arthroscopic Repair of Rotator Cuff Tears: A Retrospective Observational Study; Ann Rehabil Med 2016;40(2):252

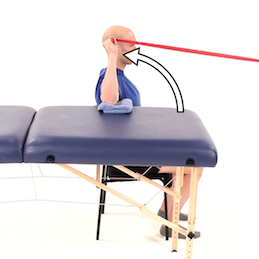

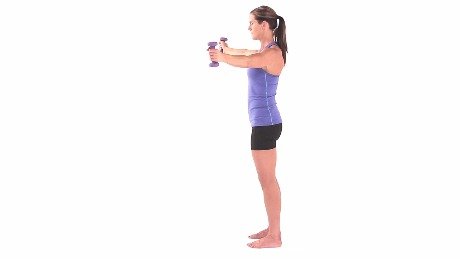

Here are a few of my favorite exercises for managing RCRSP. Know that this is not medical advice. Seek evaluation from your physical therapist for an individualized approach to managing your shoulder pain.